The Elements of Style

America's Purest Climber, Henry Barber, speaks on the morass called progress. Interview by Duane Raleigh

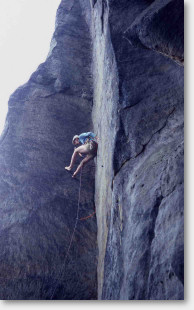

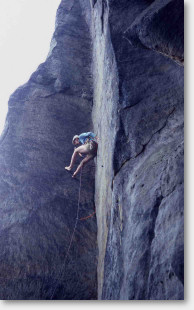

Chris Sharma wasn't even born and Dean Potter was a toddler when "Hot" Henry Barber crashed the scene in the early-1970s. During much of that decade, Barber, arguably America's boldest, most gifted and influential climber, amassed a string of first-free and on-sight solo ascents that remains unequaled in its breadth and scope, along the way redefining style and ethics on a global scale.

Barber, 50, a New England native residing in North Conway, New Hampshire, with his wife, Jill, and son, Scott, 14, began climbing in 1968, when free climbing was still struggling to define itself. During his reign, Barber climbed "320 to 350" days a year and globetrotted at an unprecedented pace, visiting virtually every developed or emergent climbing area in the world.

Admittedly fueled by competition, Barber would descend on an area and burn off the locals by bagging their projects, usually with embarrassing ease. In 1973, Barber pulled into Yosemite and, says

John Bachar, "really shook it up." On that trip, Barber knocked off a mind-bending on-sight solo of the Steck-Salathe (IV 5.9) on Sentinel Rock; climbed the Nose 75 percent free, nearly clean and in a

day and a half; and nabbed Steve Wunsch's standing project, the finger crack Butterballs (5.11c), a route that was, according to Bachar, "way over everybody's heads."

Admittedly fueled by competition, Barber would descend on an area and burn off the locals by bagging their projects, usually with embarrassing ease. In 1973, Barber pulled into Yosemite and, says

John Bachar, "really shook it up." On that trip, Barber knocked off a mind-bending on-sight solo of the Steck-Salathe (IV 5.9) on Sentinel Rock; climbed the Nose 75 percent free, nearly clean and in a

day and a half; and nabbed Steve Wunsch's standing project, the finger crack Butterballs (5.11c), a route that was, according to Bachar, "way over everybody's heads."

Barber returned to Yosemite in 1975 and again raised the stakes with Fish Crack (5.12b), the Valley's biggest prize at the time, and a project being worked by Bachar and Ron Kauk. With just Stoppers for pro and shod in clunky, stiff-soled boots, Barber climbed to the poorly protected crux near the route's end-and fell. Taking a horrendous whipper, he wrenched onto a lone, sketchy nut that, had it pulled, would have ended his bold career. After Barber's heart-stopping fall, Kauk and Bachar, "unwilling to commit to that kind of runout," gave up on the route. Barber, undaunted, returned, finished the lead, and established Yosemite's first 5.12.

Barber's lead of Fish Crack and his brassy approach toward all of his climbs, "Made the climbing world stop and say 'Holy shit, this is the next step,'" says Bachar. "Seemed like the scarier the climb, the more Barber shined. I followed in his steps, Kauk did, everyone did."

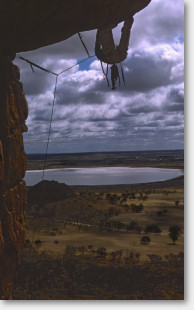

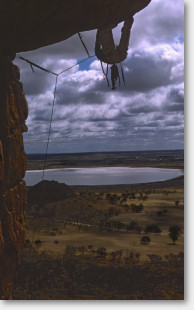

Next up was Australia, where, in 44 days, Barber blazed 67 new free routes, climbing so hard the locals couldn't even follow him. Besides introducing Australian climbers to chalk, Barber ushered in the grades of 22 (5.11c), 23 (5.11d) and 24 (5.12a). Prior to his arrival, the hardest grade had been 21.

Throughout his travels, Barber climbed in unimpeachable style, often conforming his methods to that of the area. In Dresden, Germany, in 1976, he climbed like the locals: barefoot, chalkless, eschewing metal

gear such as nuts and pins and only using jammed knots and the occasional ring bolt for protection. Berndt Arnold, then Dresden's ace climber and a Soviet "Master of Sport," still shakes his head when recalling

Barber, saying that he remains the strongest American to ever visit.

Throughout his travels, Barber climbed in unimpeachable style, often conforming his methods to that of the area. In Dresden, Germany, in 1976, he climbed like the locals: barefoot, chalkless, eschewing metal

gear such as nuts and pins and only using jammed knots and the occasional ring bolt for protection. Berndt Arnold, then Dresden's ace climber and a Soviet "Master of Sport," still shakes his head when recalling

Barber, saying that he remains the strongest American to ever visit.

Influenced by the strict ethics of Dresden and the style of climbers there, who 50 years prior to his visit had established serious 5.10s and 5.11s, Barber returned to the United States with the goal of purifying his style, saying that the perfect climb was on-sight-solo, barefoot and chalkless. He came close to achieving his goal in 1977 on Dean's Day Off (5.12a) at Independence Pass, Colorado. On this 85-degree granite hand- to fingercrack to face route, Barber spent three attempts over three days meticulously climbing up and down the technical route to avoid weighting the rope. On his final push, he unlocked the tweaky face exit, no falls, barefoot and high above a string of nuts. Today, Dean's Day Off is rarely repeated, having a reputation for being both difficult and spicy even with micro cams.

Though known for his exploits on rock, Barber was also a prolific ice climber and alpinist "well ahead of his time, with a commitment and style that was impeccable," says ice-climbing pioneer Jeff Lowe. "It even took him a long time to warm up to wrist leashes, which he considered aid. Now look at ice climbing: It's going back to leashless!"

With Rob Taylor, Barber was the first to climb the Vettisfossen, a 900-foot frozen WI 6 waterfall in Norway that, 27 years later, remains unrepeated. During a rare American visit to the Pamirs in what was then the U.S.S.R., Barber soloed a bold new 4,000-foot alpine ice route on Korea Peak (15,551 feet), a climb that was "near suicidal" due to crevasse hazards.

Though the passage of time now limits Barber's climbing to "60 to 80 days a year," it hasn't tempered his convictions, and his voice still resonates with passion and authority. As always, every climber may not see eye-to-eye with him, but all would do well to listen-Barber may be the last leading climber of his era who still cares about the future of the sport.

Continue to Part 2

Chris Sharma wasn't even born and Dean Potter was a toddler when "Hot" Henry Barber crashed the scene in the early-1970s. During much of that decade, Barber, arguably America's boldest, most gifted and influential climber, amassed a string of first-free and on-sight solo ascents that remains unequaled in its breadth and scope, along the way redefining style and ethics on a global scale.

Barber, 50, a New England native residing in North Conway, New Hampshire, with his wife, Jill, and son, Scott, 14, began climbing in 1968, when free climbing was still struggling to define itself. During his reign, Barber climbed "320 to 350" days a year and globetrotted at an unprecedented pace, visiting virtually every developed or emergent climbing area in the world.

Barber returned to Yosemite in 1975 and again raised the stakes with Fish Crack (5.12b), the Valley's biggest prize at the time, and a project being worked by Bachar and Ron Kauk. With just Stoppers for pro and shod in clunky, stiff-soled boots, Barber climbed to the poorly protected crux near the route's end-and fell. Taking a horrendous whipper, he wrenched onto a lone, sketchy nut that, had it pulled, would have ended his bold career. After Barber's heart-stopping fall, Kauk and Bachar, "unwilling to commit to that kind of runout," gave up on the route. Barber, undaunted, returned, finished the lead, and established Yosemite's first 5.12.

Barber's lead of Fish Crack and his brassy approach toward all of his climbs, "Made the climbing world stop and say 'Holy shit, this is the next step,'" says Bachar. "Seemed like the scarier the climb, the more Barber shined. I followed in his steps, Kauk did, everyone did."

Next up was Australia, where, in 44 days, Barber blazed 67 new free routes, climbing so hard the locals couldn't even follow him. Besides introducing Australian climbers to chalk, Barber ushered in the grades of 22 (5.11c), 23 (5.11d) and 24 (5.12a). Prior to his arrival, the hardest grade had been 21.

Influenced by the strict ethics of Dresden and the style of climbers there, who 50 years prior to his visit had established serious 5.10s and 5.11s, Barber returned to the United States with the goal of purifying his style, saying that the perfect climb was on-sight-solo, barefoot and chalkless. He came close to achieving his goal in 1977 on Dean's Day Off (5.12a) at Independence Pass, Colorado. On this 85-degree granite hand- to fingercrack to face route, Barber spent three attempts over three days meticulously climbing up and down the technical route to avoid weighting the rope. On his final push, he unlocked the tweaky face exit, no falls, barefoot and high above a string of nuts. Today, Dean's Day Off is rarely repeated, having a reputation for being both difficult and spicy even with micro cams.

Though known for his exploits on rock, Barber was also a prolific ice climber and alpinist "well ahead of his time, with a commitment and style that was impeccable," says ice-climbing pioneer Jeff Lowe. "It even took him a long time to warm up to wrist leashes, which he considered aid. Now look at ice climbing: It's going back to leashless!"

With Rob Taylor, Barber was the first to climb the Vettisfossen, a 900-foot frozen WI 6 waterfall in Norway that, 27 years later, remains unrepeated. During a rare American visit to the Pamirs in what was then the U.S.S.R., Barber soloed a bold new 4,000-foot alpine ice route on Korea Peak (15,551 feet), a climb that was "near suicidal" due to crevasse hazards.

Though the passage of time now limits Barber's climbing to "60 to 80 days a year," it hasn't tempered his convictions, and his voice still resonates with passion and authority. As always, every climber may not see eye-to-eye with him, but all would do well to listen-Barber may be the last leading climber of his era who still cares about the future of the sport.

Continue to Part 2